Social Media Myths of filter bubbles versus Mainstream Media and Manufacturing Consent – Crap Detection is a literacy of the Digital Environment.

Despite widespread fears that social media and other forms of algorithmically-filtered services (like search) lead to filter bubbles, we know surprisingly little about what effect social media have on people’s news diets.

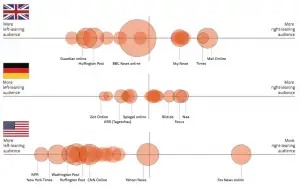

Data from the 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report can help address this. Contrary to conventional wisdom, our analysis shows that social media use is clearly associated with incidental exposure to additional sources of news that people otherwise wouldn’t use — and with more politically diverse news diets.

This matters because distributed discovery — where people find and access news via third parties, like social media, search engines, and increasingly messaging apps — is becoming a more and more important part of how people use media.

The fear of filter bubbles and the end of incidental exposure

The role social media plays varies by context and by user. For some highly engaged news lovers, it may be seen as an alternative way of accessing news that allow them to sidestep traditional brands, or as a convenient way of accessing news from multiple sources in one place.

Importantly, however, most people do not consume news online in this way. For them, the Internet — and social media in particular — is just as likely to be a means of passing the time, staying in touch with friends and family, or a source of entertainment.

Some scholars have worried that, in media environments that offer unprecedented choice, people uninterested in news will simply consume something else, with the effect of lowering knowledge, civic engagement, and political participation amongst the population as a whole.

Even for those who are interested enough to pay attention to news on social media, self-selection and ever-more responsive algorithmic selection could combine to trap people inside “filter bubbles,” where they only ever see things they like or agree with, from sources they have used in the past. The central fear, as Eli Pariser has put it, is that “news-filtering algorithms narrow what we know.”

This, at least, is the theory. These ideas, however, largely fail to take account of the potential for incidental exposure to news on social media: situations where people come across news while using media for other, non-news-related purposes. In the 20th century, incidental exposure was relatively common, as people purchased newspapers to read the non-news content, or left their televisions on between their favorite programs, and in the process, came across news without actively seeking it out. At the beginning of the 21st century, it was hard to see how this could be replicated online, leading people to conclude that incidental exposure would wane. Even as social media reintroduced this potential — by supplementing people’s active choices (accessing specific websites) with algorithmic filtering automatically offering up a range of content when people accessed a site or app — the concern was that their underlying logic would have a limiting effect on exposure by giving people more of what they already used and less of other things.

Our evidence, however, suggests that the opposite is happening on social media, at least for now. (The algorithms, of course, continually change.)

Leave a Reply