Taiwan is a promising experiment in participatory governance. But politics is blocking it from getting greater traction.

Taiwan is a promising experiment in participatory governance. But politics is blocking it from getting greater traction.

It was late in 2015, and things were at an impasse. Some four years earlier, Taiwan’s finance ministry had decided to legalize online sales of alcohol. To help it shape the new rules, the ministry had kicked off talks with alcohol merchants, e-commerce platforms, and social groups worried that online sales would make it easy for children to buy liquor. But since then they had all been talking past each other. The regulation had gotten nowhere.

That was when a group of government officials and activists decided to take the question to a new online discussion platform called vTaiwan. Starting in early March 2016, about 450 citizens went to vtaiwan.tw, proposed solutions, and voted on them.

Within a matter of weeks, they had formulated a set of recommendations. Online alcohol sales would be limited to a handful of e-commerce platforms and distributors; transactions would be by credit card only; and purchases would be collected at convenience stores, making it nearly impossible for a child to surreptitiously get hold of booze. By late April the government had incorporated the suggestions into a draft bill that it sent to parliament.

The deadlock “resolved itself almost immediately,” says Colin Megill, the CEO and cofounder of Pol.is, one of the digital platforms vTaiwan uses to host discussion. “The opposing sides had never had a chance to actually interact with each other’s ideas. When they did, it became apparent that both sides were basically willing to give the opposing side what it wanted.”

Three years after its founding, vTaiwan hasn’t exactly taken Taiwanese politics by storm. It has been used to debate only a couple of dozen bills, and the government isn’t required to heed the outcomes of those debates (though it may be if a new law passes later this year). But the system has proved useful in finding consensus on deadlocked issues such as the alcohol sales law, and its methods are now being applied to a larger consultation platform, called Join, that’s being tried out in some local government settings. The question now is whether it can be used to settle bigger policy questions at a national level—and whether it could be a model for other countries.

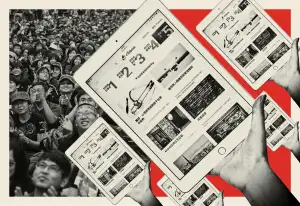

Taiwan might not seem like the most obvious place for a pioneering exercise in digital democracy. The island held its first direct presidential election only in 1996, after a century marked first by Japanese colonial rule and then by Chinese nationalist martial law. But that oppressive past has also meant that Taiwanese have a history of taking to the streets to push back against heavy-handed government. In Taiwan’s democratic era, it was a protest four years ago that planted the seed for this innovative political experiment.

The 2014 Sunflower Movement, led by students and activists, derailed an attempt by President Ma Ying-jeou’s government to ram through a trade agreement between Taiwan, which has been locally ruled since 1949, and China, which claims Taiwan as its territory. For more than three weeks the protesters occupied government buildings over the deal, which they felt would give China too much leverage over the Taiwanese economy.

In the aftermath, the Ma government invited Sunflower activists to create a platform through which it might better communicate with Taiwan’s youth. A Taiwanese civic tech community known as g0v (pronounced “Gov Zero”), which had played a leading role in the Sunflower protests, built vTaiwan in 2015 and still runs it. The platform enables citizens, civil-society organizations, experts, and elected representatives to discuss proposed laws via its website as well as in face-to-face meetings and hackathons. Its goal is to help policymakers make decisions that gain legitimacy through consultation.

Leave a Reply