Author: Robert Hoffman, Ottawa (written Jan. 11, 2007)

Author: Robert Hoffman, Ottawa (written Jan. 11, 2007)

Target setting is an important component of the policy response to the issue of climate change and the urgent need to reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases. But target setting is but one element among several in the process of public policy making. Target setting, by itself, is apt to be ineffective at best, counterproductive in some cases, and, at worst, an excuse not to address the problem at all. Target setting must be preceded by an analysis of possible pathways or scenarios, and the selection of a desired pathway. Then, once targets have been selected along the chosen pathway, the policies needed to change or direct the behaviour of economic agents can be implemented.

The domain of public policy presumes that the future is not fully pre-determined, but that it can be influenced by appropriate public policy to achieve outcomes thought to be more desirable or beneficial than alternatives.

But not all imaginable futures are realizable because we live in a world subject to laws of thermodynamics and subject to limitations of the stock accumulated of know-how. The future may be thought of as a family of possible pathways, all having a common history and starting point, but diverging from one another more as the length of time from the starting point gets longer. Because the pathways are for all intents and purposes endless, it is important to choose among pathways and not endpoints.

The elements of a public policy framework within which target setting is an important component are outlined in what follows. The framework consists of the following steps:

- identification of possible pathways

- selection of desired pathways

- analysis and application of policy instruments

- target setting

- monitoring progress

- adjusting policy

- adjusting pathway analysis

The steps in the framework outlined above are not a one-time sequence. Rather, there is feedback from later to earlier tasks in the sequence as time unfolds.

Possible Pathways

Accordingly, the first task of policy analysis is to explore the space of possible pathways into the future – possible from the perspective that they are coherent with the laws of thermodynamics and the state of know-how. The time horizon should be far enough in the future that the end of the pathway is largely independent of the starting condition. In practical terms, this means that there must be enough time for the stocks in the system to turnover at least once if not twice. For the energy system, which is the major source of anthropogenic green house gas emissions, the time horizon must be 50 to 100 years. This time horizon is long enough to allow several turnovers of energy using devices such as appliances, heating systems, and motor vehicles and at least one turnover of energy producing facilities such as electric power generating stations needed to examine pathways that lead to low carbon future.

Selecting a Pathway

Once the ensemble of possibilities has been delineated, a preferred pathway or family of pathways must be selected. This is very much a political process. In societies with representative governments, the decision-making authority has been delegated to elected representatives. The expression of choice is inevitably subjective; pathways may be valued differently by different individuals or groups of stakeholders. Those who benefit from a particular outcome may have to compensate those who disbenefit; choice involves understanding the real tradeoffs among interests and negotiating until a choice can be made that is acceptable to all parties.

Choosing Policy Instruments

Once a pathway has been selected, policy instruments must be selected and applied in such a way that the system is nudged onto the preferred pathway. The selection of policy instruments is based upon the understanding of the responsiveness of agents, whether they be energy producers or consumers, to the policy instruments chosen. A variety of policy instruments are available, ranging from suasion, to taxes, subsidies, trading schemes, regulation, and the establishment of new institutions. Of course, the policy instruments must be applied at the right time and at the appropriate intensity. For example a carbon tax will be ineffective if applied with an intensity that is too low to induce substitution or if substitutes are not available. The application of policy instruments may have unintended and unforeseen consequences that may negate its use. An example is the Jevons paradox – the proposition that technological progress that increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, tends to increase (rather than decrease) the rate of consumption of that resource. There is much uncertainty surrounding the response of agents to economic instruments. For two reasons: The first is that the policy response is usually inferred by statistical analysis of historical data and the range of experience or variation encompassed in historical data may not encompass the range needed for the future. Second, statistical analysis may not be powerful enough to separate the change in behaviour attributable to a policy from that attributable to other factors. It must be remembered that the objective of policy is to change behaviour, not to constrain the future to historical modes of behaviour.

Setting Targets

The selected pathway consists of a time series of points in a multidimensional space. Targets may be selected from this universe of points by selecting one or several time periods and by selecting from among the dimensions. For example the original Kyoto target was specified for a single year, namely 2012 and for a single dimension, namely tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions (or reductions from 1990 levels). Targets can be and perhaps should be specified along more dimensions and at shorter time intervals in order to support the comparison of actual achievements with targets. The dimensions chosen for targets should be ones for which a measurement process is place. It has to be recognized that the pathway from present to a selected target year is not necessarily a straight line. Rather, it is to be expected that the effort and investment required to effect a transition will increase green house gas emissions in the near term but will result in more significant reductions once the new infrastructures are in place.

Monitoring Progress

In order to determine whether the selected policy instruments are having their intended effect, the system performance as indicated by measures of the target variables must be compared with targets. If the target is set for a time period too far into the future, it may not be apparent that the target will be missed until it is too late to change course sufficiently for the target to be met. If targets are missed, it will be necessary to adjust pathways and targets consistent with the new starting point.

Refining Policy Instruments

Policy instruments can be adapted and refined when it becomes clear that the system is not on the targeted pathway or when the observed values of the targeted variables deviate from the targeted values. Targets may be missed for two reasons: either the policy instruments did not have the intended effect or the system was subject to unanticipated disturbances. In either case, the policy instruments need to be adjusted either by changing the intensity with which they are applied or by introducing new instruments.

Advances in Know-How

Advances in know-how resulting in deployable new technologies may open new pathways. Should new pathways be preferred, new targets will need to be set and the policy mix will have to be adjusted in such a way that they will steer the system onto the new pathway..

The Kyoto Targets

The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The major feature of the Kyoto Protocol is that it set binding targets for 37 industrialized countries and the European community for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The Protocol was initially adopted on 11 December 1997 in Kyoto, Japan and entered into force on 16 February 2005.

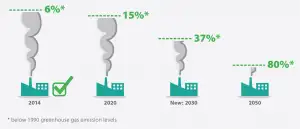

Under the Protocol, Canada, as one of 37 Annex 1 countries, committed itself to a reduction greenhouse gas emissions of 6% from the 1990 level by 2012. By 2008, Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions had in fact risen by 33% from the 1990 level. That Canada will not meet its international commitment indicates a major failure of public policy. It may be interesting to examine this failure from within the public policy framework set out above.

It is of course possible that Canada entered into the Kyoto negotiations in bad faith, never intending to meet its obligations, but this is unlikely to have been the case.

However, it is evident that the target for Canada was established in the absence of knowledge or understanding of the changes in the Canadian energy system that would be required if the targets were to be met. In the 1990’s and even to this day the Government of Canada does not have or have access to the models that would be appropriate for exploring pathways to low emissions futures that would meet the agreed upon target.

Once the 2012 target was accepted, a number of policies were put in place in the absence of any knowledge of whether the policies would be capable of pushing the energy system onto a pathway through the 2012 target. It is likely the case that policies were chosen because they were both politically feasible and could be defended as ‘steps in the right direction’. These consisted of the ‘one tonne challenge’ program that tended to shift responsibility for taking action onto individuals and ‘eco-efficiency’ programs that provided subsidsidies for those making home improvements resulting in energy savings. The most significant direct response undertaken by the government of Canada was the promotion of the use of biofuels: subsidies for the production of biofuels, primarily ethanol from grain, and a mandated share of biofuels in motor vehicle fuels. Even a cursory analysis of pathways capable of reaching the Kyoto target would have indicated that these policies would be insufficient.

The sole yardstick against which progress was to be measured was emissions in 2012. By the time it became apparent that the target would be missed, it was too late to take action that would result in Canada meeting its obligation, short of actions that would have caused major economic and social disruptions. What was needed were intermediate targets along a feasible pathway to 2012. In the absence of any pathway analysis, it was not possible to set intermediate targets and hence not possible to monitor progress and revise policy as needed.

The 2012 yardstick was also too short in time. It is possible that a pathway capable of meeting the 2012 target would not be compatible with pathways leading to much lower carbon futures – as much as 80% below 1990 levels thought by some to be necessary for climate stabilization. While it is conceivable that biofuels might have contributed to meeting the Kyoto target, it is obvious that biofuels will have little role to play in longer term low carbon futures. Arguably, the foray into biofuels has had the effect of prolonging dependence on refined petroleum fuels in motor vehicles and set back by at least a decade the penetration of electric/hydrogen powered vehicles which are essential for a low carbon future.

The response of the Government of Canada to climate change is an example of the inappropriate use of target-setting as an instrument of public policy.

——————————————————————————————

Bio: Robert Hoffman is one of the seven Canadian Members of the Club of Rome. He is President of whatIf? Technologies Inc., a company that has modelled energy systems for Canada.

Leave a Reply