If You don’t like it Leave! My way or the Highway.

Get yours now . Make piracy great again. Win at all costs and keep the spoils.

Maybe other ethics should be considered and how to define and sustain social justice.

The following article contributes to the dialogue on solutions.

People who happen to be alive at historic turning points are often slow in sizing up these major shifts. It’s natural for the human brain to rely on familiar ways of thinking to make sense of what’s new. Just think of how the first cars were described as “horseless carriages” and cinemas as “motion-picture theatres”.

As we approach the 2020s, there’s growing evidence that we’re at a historic crisis point for modern democracies and pluralist societies. Political systems across the world are simultaneously experiencing deep disruption, with a startling escalation of polarization and tribalism. Cast your eyes across nations as diverse as the US, France, Germany, the UK, Italy, Hungary, Austria, Sweden, Poland, Brazil and the Philippines. In each of these countries we see similar patterns: public frustration with the status quo, populist insurgencies, the division of groups into “us-vs-them”, political deadlock, attacks on democratic norms and a sense that meritocracy and rational policy-making are increasingly passé. Since the Second World War, many democratic countries have experienced divisive flashpoints, but there is something unique in the postwar era about the way pluralism and democracy are simultaneously under siege in so many places.

Yet we are struggling to make sense of it. By default, observers often define these developments through the familiar lens of election results and left vs right politics: a “shift to the right” or “rise of the far right”. But much more is at play. Issues of identity, belonging and tribalism are supplanting the longstanding left vs right spectrum once defined by attitudes towards the size of government and intervention in free markets.

Deepening distrust

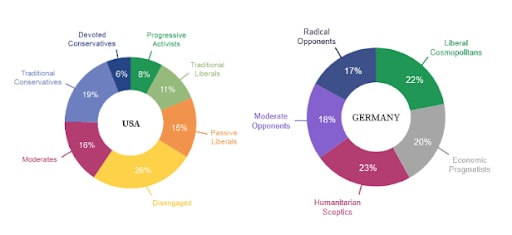

For the past three years, More in Common has been analysing public attitudes in established democracies to better understand the forces that are driving us apart, and what can bring us back together. Working with social psychologists and leading market research firms, we have commissioned detailed national studies in the US, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Greece. These studies create a national segmentation based on people’s core beliefs and tribal attachments. (To identify which of America’s “hidden tribes” you might belong to, you can take a sample quiz here.)

The picture emerging from these studies shows more than just shifts in public opinion about specific issues. There is a deepening distrust in each other – not just in institutions – with growing tribalism and intolerance of those with different beliefs and backgrounds. Multiple centrifugal forces are driving societies apart, and few of these forces are unique to any one country. Economic factors are playing a central role: rising inequality, stagnant incomes, job insecurity and the division between prosperous cities and “left behind” regions. But the perfect storm of conditions for social fragmentation come about from the convergence of economic forces and changes in culture, technology and the media landscape. Against a backdrop of weaker social connectedness and the erosion of local community life, these forces often play into existing faultlines in societies – widening racial, religious and ideological divisions.

The more polarized a society, the more people view difficult issues through a tribal lens rather than in terms of the common good of all. This makes pluralist societies less resilient, more vulnerable to social stresses, and less able to navigate the typical 21st-century crises such as political deadlock, rapid demographic change, economic slumps, climate events, technological change and threats to national security.

National segmentation studies in the US and Germany, 2017-2019

The most troubling conversations I had in the past year were with experts in conflict prevention, who look at the deepening polarization in the United States and see patterns that in other societies have led to widespread civil violence. Whether you see that as realistic or alarmist, we should never take it for granted that societies always have the resilience to withstand the forces of division. Building and sustaining resilience to social stress is hard work. One of the great accomplishments of democracies is how they have made it look so easy for so long. But in reality, maintaining the rule of law, accountable institutions, independent media, social trust and strong civil society networks is immensely complex. Advanced democracies have not only struggled to build democratic infrastructure in countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq; at home, they have been eating into their social capital, and failing to replenish it.

A proactive agenda

We need to do much more than cross our fingers and hope for a swarm of political candidates with the supernatural formula of personal charisma, strategic smarts and a captivating agenda to counter the divisive forces of authoritarian populism. We need to rebuild our social capital and strengthen the centripetal forces that can counter the appeal of us-vs-them tribalism.

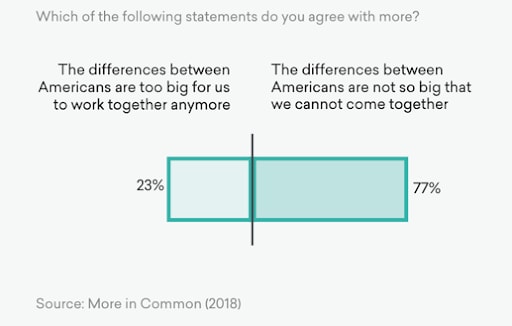

This is a profound long-term challenge. But one reason for hope is that even in deeply divided countries such as the US, people have not given up on believing their divisions can be overcome. More in Common found late last year that 87% of Americans believe the United States is more divided than at any point in their lifetimes. Yet 77% of them also believe that their differences are not so great that they cannot be overcome.

So what does a proactive agenda to reverse polarization look like?

We need champions of innovation in every walk of life to turn their skills towards the challenge of rebuilding social trust and connection across the lines that divide us: city from country, brown from white, conservative from liberal, Christian from Muslim, new immigrant from native citizen, unskilled from graduate, cosmopolitan from town-dweller. At the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Councils last November in Dubai, lively conversations were sparked as we imagined what might be achieved if we turned our extraordinary human capacity for ingenuity and innovation towards the increasingly urgent global challenge of countering polarization. There is a potentially powerful role for the World Economic Forum in shining a light on what is working best.

It means a fresh lens for policy-making, seeking to develop policies that counter deepening social fractures and address the insecurities that make people vulnerable to us-vs-them narratives. Strengthening social contact is a start. For example, how can urban planning, housing and schooling policies counter the segregation of people into clusters of homogenous wealth, racial and ideological groupings? In labour market policy, amid automation, robotics and artificial intelligence, how do we build people’s confidence that their hard work will be rewarded and address fears that the rug is soon going to be pulled from under them?

For the tech sector, this means reworking business models that, however unintendedly, disseminate misinformation, exploit psychological vulnerabilities and provide a platform for extremists. But we cannot expect the sector to get its house in order by itself. Regulators must play their part in strengthening incentives for social media platforms to take their impact on democracy and social cohesion far more seriously. Tech firms must embrace greater transparency and accountability.

For political leaders and civil society, this means reinvigorating representative democracy in ways that make it more relevant to new generations. We need low-barrier ways to engage ordinary citizens more meaningfully, not just the loudest voices with the most strident views. We must also rethink the incentives that reward those politicians, advocates and campaigners who pursue victory at any cost – too often at the price of belittling opponents and undermining wider public trust in the system.

For culture and the arts, this means doing more to promote empathy and understanding across lines of division. For example, while reality television is often linked to conflict, trivia and vulgarity, the genre also creates opportunities to foster empathy by exposing us to people with different backgrounds and beliefs to ours. Deliberative opinion polls and citizens’ assemblies show that even people from opposing viewpoints and backgrounds consistently find common ground when brought together to solve a problem. Politics and a media driven by the “attention economy” are providing fewer real-world examples of how this can work. Perhaps the entertainment industry can step into this gap.

Have you read?

When we entered a new century almost two decades ago, few in advanced democracies were anticipating the turn of events that has led to deepening social fractures and democratic crisis. As a result, we allowed our systems and institutions to atrophy. We have begun to pay a price for this neglect, but that price could yet become much greater. We all have a stake in ensuring that pluralist societies are resilient to the threats of division, tribalism and systemic breakdown. We need a resolve to combat polarization, new coalitions to provide leadership and a much stronger ecosystem of initiatives to awaken us all to the threat of deepening divisions, to rebuild our social capital and renew public confidence that free and democratic societies are best placed to advance the common good of all.

Tim Dixon is a co-founder of More in Common, based between London and New York. He has served as senior adviser to two Australian prime ministers.

Leave a Reply