By David Wallace-Wells

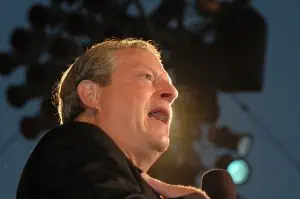

It would probably have been tempting, talking to Al Gore at any point over the 18 years — after 9/11, in the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq, in the depths of the financial crisis, as Obama failed to pass climate legislation and pushed the Clean Power Plan instead — to wonder what might have been. And what it must be like to be him, and, looking out at the world, wonder the same.

It would probably have been tempting, talking to Al Gore at any point over the 18 years — after 9/11, in the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq, in the depths of the financial crisis, as Obama failed to pass climate legislation and pushed the Clean Power Plan instead — to wonder what might have been. And what it must be like to be him, and, looking out at the world, wonder the same.

But the presidency of Donald Trump — which happens to coincide with a kind of “crisis” for the internet, one of his signature subjects, and a growing public appreciation for the planetary peril of global warming, his other — is an especially glaring prompt. And Trump does seem to be very much on Gore’s mind, too; he brought him up three separate times when I sat down with him last week, in New York, just ahead of his annual, 24 Hours of Reality special television event — an around-the-clock and around-the-globe climate change program which begins tonight at 9 p.m. This year’s broadcast, based in California, is focused on public health — which is all of a sudden a bigger and bigger part of the way scientists and climate advocates are talking about the threat from warming.

It’s interesting to talk about the California fires in this context, since one of the underappreciated aspects of that is the public health element.

For most of the week, the four most polluted cities in the world were Sacramento, San Francisco, San Jose, and Chico, worse than any cities in India.

And when you know what Delhi looks like, that’s really bad.

Absolutely. And you covered it in a recent article: the cognitive impacts, the particulate pollution.

Five, ten years ago, public health wasn’t even such a big part of the way that people talk about climate. What changed?

The health consequences turn out to be a very effective lever to move public opinion on climate.

I had an experience about two years ago when, just prior to the election of 2016, the Centers for Disease Control scheduled a major conference on climate and health in Atlanta. Do you know this story?

I don’t.

Before the election, they scheduled this major conference and they reached out and asked me to give the opening keynote, which was something I regarded as an honor. But when Trump won the election, the CDC apparently panicked and canceled the conference. They had had an unpleasant experience with Congress the year before when they had a conference on guns as a public-health issue. And the Congress cut $16, $17 million out of their budget, which corresponded with what they were spending on that issue. I think they were afraid they were gonna have a repeat of that.

It struck me as kind of a chicken move. So I called President Carter and asked if I could have his Carter Center for the day of the conference and he said sure. And I called Ted Turner and asked if he would underwrite it, and he said sure. And so then I called the people who were gonna be at the CDC conference, and they all said, yeah, we’ll come anyway. And then the CDC experts took personal leave to come over.

That was an opportunity for me to dig more deeply into dimensions of this nexus that I had not spent as much time on previously. And the more I looked, the more shocked I was at how pervasive the health effects are. When the Obama White House, in President Obama’s second term, got in gear on climate and particularly when they introduced the Clean Power Plan, they had, obviously, done a lot of polling and political analyses and had decided to put the health consequences as their lead item. And, I thought, yeah, that makes sense.

I guess in the past, I have been so focused, and still am, so focused on the global existential crisis that just teasing out one part of it seems like a bow to the political polling reality. But, look, why not? Let’s engage people however we can do so most effectively.

Yeah, it seems to me that, so often, when people hear about it as a global crisis, they almost think, well, it’s happening elsewhere, I can avoid it. And something about health really feels immediate, like it’s going to affect your lungs, your mother’s lungs, your children …

And the health consequences are, of course, pervasive.

I mean, the numbers are staggering. It’s deaths every year in the millions from air pollution and …

Nine million is now kind of a baseline. It’s probably higher than that. You hear the phrase, now, air pollution is the new smoking.

I’ve been thinking about it in terms of lead. We now see all of these interesting consequences of the lead pollution in the mid-century. Every year there’s more stuff about criminality and mental illness. And it sort of seems a similar thing with air pollution. It’ll affect anybody with respiratory illness — okay. But there are also all of these more surprising effects — on schizophrenia, on autism. It almost seems like there’s nothing you might worry about that it doesn’t impact negatively.

And lead is the other pervasive, long-lasting pollution besides CO2. And the difference is, it can’t really be removed. Are we going to acquiesce in creating a reality where, from now until the end of time, we have to warn pregnant women and women of childbearing years that they can’t eat fish? And that they have to really be scared to eat fish? Really? Are we gonna create that permanent reality for all future generations? Apparently, we’re on track to do that.

We have taken some steps, but the biggest single source is burning coal, and so it’s yet another horror linked with this dirty fuel source.

One thing that strikes me as different about air pollution is there is this sort of grotesque trade-off with climate. There are these studies that show that the existing aerosol pollution is suppressing global temperatures by maybe as much as half a degree.

Yeah, I don’t really see that as being as much of a dilemma. It’s a co-pollutant. You get rid of CO2, you’re going to get rid of most of the aerosol pollution anyway, and we might as well face the reality of what we’re doing instead of masking it to a slight degree with the pollution. If the choice is more air pollution in order to get a slight dampening of the otherwise rapidly increasing temperatures, I don’t see that as a dilemma.

Leave a Reply