Author: Edward W. (Ted) Manning, Ottawa.

Based on several research projects by Dr Edward W. (Ted) Manning, President, Tourisk Inc. focused on green development in islands and coastal zones and a report prepared as input to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) on Green Economy.

Executive Summary

- Tourism ls now one of the largest industries on the planet, and has great potential to stimulate the green economy in SIDS. Tourism is vital to most SIDS, either current or potential, with huge economic impact and importance; for many SIDS it is their largest source of foreign exchange and the driver of their development. Achieving levels of sustainability in tourism development has long-term benefits to both investor, hotel chains and local stakeholders.

- The consequences of tourism can be either positive or negative. Tourism contributes to the national balance of payments and the creation of jobs, but it also creates enormous pressure on environment and energy resources as well as having impacts on the local culture.

- It is in the interest of the tourism industry to sustain the destinations it targets. In many SIDS, tourism is the principal economic sector and its approach to development will sustain or harm the destination. International tourists and cruise passengers can outnumber inhabitants of SIDS (in some cases on a single day) and their choices have significant impact on the destinations and on tourism sites. Action to sustain SIDS as attractive destinations will benefit both tourists and locals.

- Integrated planning of destinations incorporating tourism is essential. For many SIDS the boundaries of the state and the destination are the same, and tourism is the predominant economic sector. To benefit to the greatest extent possible from the green economy SIDS will need to adopt comprehensive tourism planning embedded in their national planning process and where appropriate fully integrated with an overall national plan.

- SIDS have many disadvantages in location, size and institutions which can act as barriers to the acquisition and adoption of best environmental practice in their tourism industry. It will be important to examine the means by which each state can better understand its own situation and review the barriers to taking advantage of the green economy, including legal and regulatory barriers to use of new technologies.

- More than many other destinations, the reduction of consumption of energy and water resources in SIDS can be very economically attractive. There are many success stories from SIDS where the international hotel and resort industry is adopting state of the art methods to reduce energy and water consumption. Where these resources are most constrained, the attractiveness of efficient alternatives including conservation can be amplified. Best practice in some resorts in SIDS (e.g., chains like Banyan Tree, Six Senses) can be models for others.

- While many large international tourism companies are adopting better practices which bring environmental benefits, these practices are not generally being adopted by the smaller firms, particularly in developing states. While international firms may have access to best practice through the company, smaller firms in SIDS have disadvantages associated with scale and distance from suppliers and expertise which are obstacles to obtaining information about and adopting new technologies and improved management practices associated with the green economy. Many firms are also realizing that the ecological advantages associated with reduction of negative impacts are a benefit, reducing the risk of damage to the ecosystems and attractions on which their success is built. Sharing of this among industry players is not strong.

- There are potential benefits from cooperation among SIDS. Together small states will have greater leverage in negotiation with international companies, in setting standards and in obtaining access to best practice, particularly in areas like the Caribbean or South Pacific where they share the same tourism market. There are also significant potential advantages for SIDS to work together to deal with the large resort and cruise line corporations, transport sector and tour operators, international agencies and NGOs aimed at obtaining their help in greening the destinations and at establishing compatible regulatory frameworks and standards.

- Documentation and exchange of success stories among SIDS will be important. There are many examples of best practice now available within SIDS and suitable to their needs. There is limited effective exchange now of expertise or examples and this needs to be improved.

1. INTRODUCTION: Tourism as a critical building block for sustainability in Small Islands

For most SIDS tourism is a key sector of their economy. In more than half, it is the most important source of foreign exchange. It is also for many the main engine of growth and the source of demands on natural resources, infrastructure and services. For some SIDS the number of tourists on the island can significantly outnumber all residents in peak tourist season.

Tourism globally is a very complex and fragmented business. It manages what is the largest migration in human history – every year. The supply chain stretches from the cities of the first world all the way to the most distant islands on the planet. As such it involves many players – at source, in transport and in the destination. Firms range from tiny agencies specializing in, for example, small diving vacations through to global players organizing, transporting, feeding and accommodating thousands at a time. The UN World Tourism Organization, through satellite tourism accounting, has attempted to analyze which employment and other benefits derive directly and indirectly from tourism. This is not easy, as part of the income for many occupations from taxi drivers to café owners to the convenience store near the dock are attributable to tourism while the rest is with local purchasers. In some destinations, many of these basic services would not exist at all without the tourists. This complexity carries over into most SIDS.

Typically, the core of SIDS tourism has two main components – land based tourism and cruise tourism. The main elements include:

- Large resort properties and hotels which cater mostly to package tourism. Some, like Atlantis in Bahamas, many Sandals properties, Club Med, Bahia Principe, Breezes or Intercontinental have resort properties on many islands. Some resorts have more than a thousand rooms. Many are all inclusive – meaning that tourists pay one fee for nearly all amenities and many may never leave the property. In fact, some SIDS resorts actively discourage tourists to leave the property except on guided tours which they provide, often for security purposes in destinations where public safety can be an issue. Most employ local staff for most jobs although management is most likely to be international and employed by a management company based outside the SIDS. Some intentionally import labour from other countries where there is a more advanced service culture (e.g. Sri Lankan service staff in Maldive Island resorts)

- Business hotels – generally medium sized and catering to both package tourists and a broader range of business representatives and independent travellers. Some provide food services in the property. Some are linked to chains like Best Western or Sofitel, but local hotels can often compete successfully.

- Small hotel properties, in most SIDS locally owned and catering primarily to independent travelers.

- Cruise ports and related services. Caribbean SIDS are the targets of a significant part of the world’s cruise tourism and support a range of tourist services (but not extensive accommodation). Most SIDS receive at least some cruise visits and more are expected to participate in hosting cruises as the global cruise industry seeks new ports and different experiences.

- Except in larger cruise ports or destination resorts where chain properties like Planet Hollywood or Margarita Ville can be found – catering to the lunch crowd from the ships or the tourists from the hotel strip: these are often franchises which are locally owned and employ local staff.

- Tourist services (craft shops, transportation services like taxis and tour buses, casinos, souvenir sales).There is a division between chains like Diamonds International and local shops. Most engage local staff but some of the chain shops in very seasonal centers transfer their staff to where the cruise ships go in off season.

The challenge to make SIDS tourism more sustainable will involve all these components in actions which are beneficial to the economy, environment and society of each state.

The fragmentation of the tourism industry has made greening the industry as a whole, or for entire destinations like SIDS very difficult. While many large chain hotels have adopted best practices system-wide (for example Six Senses, Banyan Tree, Fairmont, Ramada and Intercontinental among others have environmental policies, environmental officers in each resort, and commitment to much good practice) neither the understanding nor the technical expertise is present in other segments of the industry. While a Half Moon Bay Hotel in Jamaica can receive certification (e.g. Green Globe) or a Turtle Beach Fiji can be given international recognition for best practice, just a short distance down the beach, other properties have no such programs. Nor is it easy for them to obtain information or technical assistance, although in some destinations the larger chains have been known to host workshops for other properties that share the same beachfront and have a stake in its environmental quality.

As with most developing states, the local environmental management capacity in most SIDS is limited. Even when a hotel property wishes to obtain expertise to green the property, to choose suitable technologies, to do an environmental audit, or to handle a certification process this is unlikely to be locally available, (with a few notable exceptions like Singapore)..Thus, even when there is an interest in becoming more environmentally sustainable, there are logistic and economic barriers which are significant, and which are more expensive to deal with than in larger developed states. In Europe or North America, the expert can often visit for the day and return home for dinner. In Tuvalu or Sao Tome e Principe someone must pay the air fare, many days stay away from home and the costs of transport of any equipment to the site. In most SIDS, there may not even be a professor or technician who can help scope the problem or write the specifications for hiring expert advice – or even evaluate proposals. These can be significant barriers to adoption of more sustainable approaches and products.

For many SIDS their social, economic and environmental wellbeing is tied strongly to the fate of a single sector: tourism. In 2007 tourism accounted for 51% of the total value of exports from SIDS and international tourism receipts constituted more than half of the value of exports for 12 SIDS (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2010 p.16.) (e.g., 40% of ‘GDP in Seychelles, more than 30% of GDP in Bahamas and Barbados in 2007) (World Bank Development Indicators 2010). Because of its relative magnitude in many SIDS the sector has incredible potential for both positive and negative impacts and for leveraging the transformation to a green economy. (See table 2 at end article). While SIDS tourism can be based on many factors including uniqueness, exotic character and luxury, much SIDS tourism focuses on many of the most fragile environments such as beaches, reefs and unique ecosystems as the key draw. As global tourism grows and interest in visiting new places expands, more tourists choose to visit small islands, even those far from the source of the visitors. (St Helena is now accessible by air as of 2015; Cuba is now accessible by cruise ship or air to American tourists in 2016). As a consequence, tourism has become a key driver of development in many SIDS from the Maldives to Samoa to the Caribbean. Many islands have competed aggressively for cruise visits and the rapid growth of cruise tourism has a made many small island states ports for frequent visits by larger ships, often concentrated in relatively short peak seasons which coincide with the peak season for land-based tourism.

Several aspects of the tourism sector affect its current and potential role in development in SIDS, the tourism industry is seasonal. For most SIDS, arrivals are keyed to seasons both in the destination and the source. For example, high season in the Caribbean is when the weather is warm and dry in the region and is cold and unpleasant in North America and Europe. Low season is hurricane season and when weather is pleasant in the source regions. Similar patterns can be found in tourism in most SIDS. The need for infrastructure is therefore very seasonal and often significantly greater in peak seasons than low seasons. (Note that this has repercussions across all utilities and services – energy, water, waste, policing, social and health services, and transport facilities.) This means that the ability to raise revenues for investment in infrastructure (whether environmentally sound or not) is reduced and that the need for infrastructure is often concentrated in peak season, reducing investment efficiency. Where tourists may outnumber residents in peak season, the impact on infrastructure needs can overshadow service of domestic needs. (Although in principle it can be an engine to improve local services and infrastructure.)

Tourism is heavily energy dependent (mainly fossil fuels) both in travel and in consumption in the destination. Most SIDS are located a considerable distance from the source of most of their tourists. For example, the most frequent visitors to the Maldives are from Europe, for Seychelles from Britain, for Northern Marianas from Japan, for Cuba from Canada and Spain, and for most Caribbean destinations from northern cities in North America and cities in Brazil. Most visitors travel more than four hours and many much longer, particularly to destinations like Fiji, Mauritius or Grenada. Very few are short-haul (Bahamas is an exception but even so, most of its arrivals are from more than 2 hours’ flight away) and therefore seldom able to attract visitors for visits of less than a week. It should be noted as well that direct air routes are important – visitors from urban centers are more likely to choose destinations where there are direct scheduled or charter flights: the marketing of such destinations is also strongly focused on those accessible by direct flights. While charter flights are usually full, therefore consuming less fuel per passenger than many scheduled flights, even so, the ecological footprint is high, and the tourism in these destinations very vulnerable to the pricing of fossil fuels.

In the destination tourists normally use significantly more energy and water than do local residents, but also have the capacity to pay for it. Many SIDS have very limited water supplies and most must import all of the fossil fuels which they consume. (Notable exceptions include Cuba, Trinidad and SIDS such as Netherlands Antilles and Singapore which provide refinery capacity to other nations.) In those countries where reticulated water supply is not available to all, tourists can consume more than ten times the water per day than locals and there is also a large differential in per capita energy use for climate control, lighting and tours. (UNESCO Water e-Newsletter No. 155: WATER AND TOURISM). “Luxury resorts on an East African island are estimated to use up to 2,000 litres of water per tourist per day, almost 70 times more than the average daily domestic consumption of local people (Gössling and Hall 2006, cited in Green Economy 2010 p 418.)

Increasing use of air conditioning to improve levels of comfort (and in some cases extend the season) and increased use of desalinization plants for provision of water have also increased demand for energy. There are often significant cost reductions for tourism enterprises that adopt best practices for water and energy use – particularly in those SIDS where both resources are in short supply or expensive. As well, most new technologies and practices require up-front investments and may require retro-fits. This can be a strong incentive to reduce energy or water consumption. For new builds, high ongoing energy costs may actually make such investments more attractive than in places where energy is cheap.

Tourism impacts key ecosystems because the focus of its activities is often concentrated on the most sensitive sites. Tourists visit because of the reefs, the beaches, the unique cultures and ecosystems. The effects of tourism are disproportionately concentrated on these sites and dependent upon them being sustained. Without suitable planning and management, tourism can be the agent for destruction of the resources on which it depends. At the same time there is advantage for firms benefiting from these resources which could be converted into an impetus to help conserve or protect them.

The tourism industry is potentially a significant vehicle through which a destination can obtain both capital and operating funds given its importance to many SIDS. In most SIDS the industry is also largely dominated by firms which are not based in the country, many being part of large international hotel chains, transportation firms, cruise lines and purveyors of tourist goods such as jewelry, electronics and souvenirs. New infrastructure is often initiated as a response to anticipated or realized tourism arrivals – and there is a challenge to governments to obtain participation by these international firms in funding that infrastructure.

Destinations are in competition for tourism. Individual SIDS have limited leverage to ask for or require funds from the tourism industry for social and environmental investments such as schools or hospitals (the latter a service which is used by tourists and may be a requirement for some tour operators to bring tours). While some islands have been successful in obtaining participation by resort chains or cruise lines in the financing of infrastructure (for example ports and portside shopping facilities) most have had limited success in obtaining investment for facilities used by the tourists. In other cases, attempts to obtain additional taxes or landing fees have resulted in Cruise lines reducing visits or investment in resorts diminishing in favor of alternatives with lower costs.

There is a growing niche tourism which stresses clean green experiences. In the 2010 Green Economy report, it was noted that more than a third of travellers were found to favor environmentally-friendly tourism and said that they were willing to pay for related experiences. SIDS which have a reputation as being relatively pristine have a comparative advantage in attracting those who seek what are often called ecotourism experiences. Ecotourism is defined by the International Ecotourism Society as “responsible travel to natural areas tha conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people” (TIES 1990): Dominica, Seychelles, and Guyana are examples of SIDS where a green image is an asset and which have begun to benefit from the growth in the market for ecological experiences. Some of the winners of international contests for best eco-resort are located in SIDS – for example Soneva Fushi Maldives and Concordia Eco-tents in USVI are both listed by National Geographic as among the World’s top eco lodges. These are examples of low impact accommodation and like most of the lodges in the list have active programs to assist in wildlife and habitat protection as part of their programs. At the same time the greening of tourism involves the reduction of the impact of more conventional hotels and resorts and other parts of the industry, including transport and other services.

There are many niche markets which are low consumption and low impact – for example birdwatchers, photographers, cultural tourists, which are likely to be beneficial to the host. For example, “life-lister” birdwatchers will travel long distances to be able to spot a new species – and actively seek new ecosystems. This niche is known to be less price sensitive than most, willing to spend large sums for a chance at a new species to add to their life list. Much of this money often goes to guides, small local lodges and long stays in rural and remote areas, and is sometimes an active contributor to the conservation of the ecosystems used.

Cruise tourism has different environmental effects than other tourism – both positive (ships bring their own water and produce their own power, many even when docked) and negative (ships concentrate large numbers for short periods on specific communities and sites). Common means to monitor tourism (bed nights, occupancy rates) normally do not capture cruise tourism which tends to be day tourism (most ships spend the night at sea, arriving in the morning at the next port) and has different multipliers for most goods and services than longer stay tourism. (Manning, 2011)

The range of tourism development in and impacts on SIDS is very broad – from Sint Maartin Netherlands Antilles with densely developed beaches and up to seven mega-ships visiting a day to Timor Leste, Tuvalu or Haiti where tourism is in its infancy.

Up to seven large cruise ships can visit the tiny Port of Philipsburg, Sint Maartin in a single day

- Challenges and Opportunities

Greening tourism means more than just providing ecotourism experiences. It also means taking actions to address reduction of risk to tourism enterprises, facilities, infrastructure and to tourists themselves. It involves anticipating and acting to prevent or mitigate natural hazards and climate change and degradation of ecosystems and harm to society or economic capacity. It also requires effort to reduce the ecological footprint of the entire sector, including mass tourism and actions which promote ecologically friendly behavior when visiting attractions and living experiences in fragile ecosystems and other tourism destinations. It also means working with the industry to ensure the skills and information necessary to deliver sustainable tourism experiences is present. Because of their size, SIDS can be a concentrated laboratory – a pressure cooker for the effects of tourism and of efforts to manage these impacts – with both positive and negative results. In fact small islands like Tenerife in the Canaries, Mallorca and Jersey have been used as “observatories” of sustainable tourism and are among the destinations where most is known about the relationships between tourism and sustainability of destinations. (Govern de las Illes Balears website). Some of what has been learned can likely be of use to SIDS. The use of SIDS as a focus for more integrated research on the relationship between tourism and overall sustainability needs to be encouraged, possibly in a similar form to the observatories cited above.

2.1 Tourism: Driving Forces

While the drivers identified in Annex 2 of the Tourism section of the Green Economy report (UNEP 2011) are all pertinent to SIDS; for most, the impact is amplified by the importance of tourism to the country and by limited capacity to respond due both to resource constraints and to other capacity limitations. (See Table 1)

Demands by tourists are becoming more sophisticated. Even vacations which feature two or three star accommodations are now expected to provide air conditioning, pools as well as beaches, satellite TV with channels from the tourists’ home countries, and water available 24 hours a day. Mechanisms to pass the real cost of consumption visibly to tourists is still lacking, despite some successes mainly in the European market to provide information on the footprint of tours to the consumer. Resource consumption by tourists normally exceeds that per capita by locals in SIDS who do not normally require air conditioning, several showers a day, swimming pools and golf courses. All of these lead to higher per capita demand for energy and water. If a resort adds water parks or fountains these significantly add to the demand per capita. Recent studies on GHG reduction for a large hotel chain have shown that some resorts consume up to1600 KBtu and 4000 litres of water per occupied room day while best practice in the Maldives can produce results of less than 200 litres per occupied room day and a new-build hotel in California has a consumption of electricity of only 108KBtu per day.

Table 1: Key Drivers and their Implications for SIDS (Based on Green Economy Drivers from UNEP)

| Key Drivers for SIDS | Likely Implications |

| Energy

· Increased energy costs · Likely carbon surcharges · Customer expectations · New low-carbon technologies · Renewable options |

· As most SIDS import nearly all hydrocarbons and few have hydroelectric or geothermal options available, the pressure for improved energy efficiency and solar/wind or even tidal options will grow. Most SIDS are located in areas with good solar potential.

· Tourism sector will feel pressure to adopt high efficiency systems, demand reduction strategies · Solar has good potential – and best capacity is usually in peak tourism season (sunny) providing suitable technologies and appropriate technological expertise suited to local (e.g., tropical climes is available) · Long- haul nature of most SIDS tourism may see weakening of demand in the face of rising fuel costs |

| Climate change

· Customer concern about reducing carbon footprint · Most SIDS are among most vulnerable states/destinations with most tourist infrastructure in vulnerable zones · Most SIDS in areas likely to be affected by extreme storm events such as typhoons, hurricanes |

· SIDS most distant from source of tourists may be at disadvantage due to cost and changing market · Tourist enterprises will be important to lead initiatives for adaptation – if only to protect its own infrastructure. · Emergency response planning will become more important · Most SIDS are not strong potential markets to receive offsets for carbon paid by tourists (small, few areas for e.g., new forests, wetland preservation relative to other countries) |

| Water

· Water scarcity is important for most SIDS. Peak tourist season in most SIDS is the season of least rainfall. · For many SIDS, small freshwater aquifers are the critical reservoir and can be easily depleted if exploited for tourism or other development using water |

· Strong impetus for efficient water management and conservation, use of recovery methods, grey water systems

· Cost of water is a key factor – many resorts use fossil fuels for desalinization systems so real costs are very evident. · In some states, there is a growing competition between tourism and communities for water resources · water supply limits may cap tourism development in some SIDS or eliminate attractions such as water parks and golf courses (also related to energy costs for pumping, desalinization) |

| Waste

· Increased expectations that destinations will be clean. · Increased costs for suitable waste management

|

· Need to address scarcity of disposal facilities in many islands – space and risk of contamination of freshwater sources and energy recovery from waste

· Measures to reduce waste produced by tourists and tourism businesses · Increased awareness and promotion of measures encouraging reduction and recycling of waste · Where there Is reticulation and/or treatment, effluent disposal at sea may mean draining aquifers · Because of significance, new tourism enterprise may be key partner in obtaining reticulation and treatment facilities and in solid waste collection and disposal facilities (and help in regular waste removal from beaches – both public and private · Tourism may be catalyst for addressing pollution and water quality in SIDS – clean water supply sources or for pure water bottling facilities |

| Biodiversity

· Reefs, beaches, fragile habitats are the principal reason for visitors to most SIDS. Unique fauna and flora of insular destinations is a growing draw. · Because of small size, SIDS tourism development is likely to be on or near fragile coastal and other fragile ecosystems |

· Demand for nature based tourism is likely to grow and to target unique species – many of which are unique to islands.

· Improved design of tourism infrastructure on targeted sites (including those stressed by cruise tours) · Need for integration of overall development/land use planning and tourism planning, including specific plans for targeted tourism hot spots. · Promotion of visitor management programs including relevant infrastructure training of managers and awareness for tourists |

| Cultural heritage

· Increased demand for opportunity to visit traditional cultures – at peril due to volume of tourism relative to small island populations |

· Opportunity to package cultural heritage (like Brimstone Hill, St Kitts, Musical experiences in Seychelles, Caribbean, culinary experiences in, Mauritius, with the dominant sea and sun which is the principal tourism for most SIDS. Significant opportunity to involve willing traditional communities (e.g., Carib in Dominica, Maya in Belize, traditional Samoan or Fijian communities) in tourism offer and to provide support to local communities |

| Linkages with Local Economy

· In those destinations with large scale resort or cruise tourism, need to involve local community in tours, provision of goods and services · Pressures to purchase food locally for hotels resorts and ships |

· Foreign exchange leakage remains a key issue for SIDS. (except Singapore and Bahrain) For most SIDS, nearly all food and drink consumed by tourists is imported, and many others rely on foreign food sources for most consumed on the island(s), (e.g. Antigua, Netherlands Antilles, Maldives). Because much import is directly for sale to tourists and much of the industry is foreign owned, there is often limited leverage to affect what is imported, from where or whether or not it is environmentally sustainable (Cruise lines and major hotel chains may use central procurement – the bananas eaten by cruisers on board while docked in Dominica were likely loaded in Miami and harvested in Costa Rica.)

· Most of the materials and skills needed to design, install and maintain new green options are not available on the island. |

Among the destinations with the most rapid tourism growth since 2000 are several of the Small Island Developing States. In particular, resort development and for other than accommodation, cruise tourism are the sectors which are powering this growth in many SIDS, most notable those in the Caribbean. Beaches in islands like Dominican Republic, Aruba, and Mauritius have significant tourism development occurring, much in the form of large scale destination resorts. While this does bring investment, it also may stress infrastructure and require additional investment to provide it. This may provide an opportunity to create more efficient water and energy supply systems.

The link between origins of tourists and SIDS destinations is affected by the pattern of direct flights. Dozens of charter and scheduled flights leave every weekend from major cities of North America, Europe and Asia for the beaches and experiences of the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean. For example, more than twenty planes leave Canadian cities alone directly for Cuban airports every Sunday in the December to March peak season, and continued to do so with little reduction during the 2008-2012 global recession. The cities of origin of tourists for islands like the Seychelles or Mauritius, are influenced strongly by the existence of direct flights – both scheduled and charter, from European cities. The European market has led others in the marketing of green tourism experiences and European operators have become a catalyst for packaging “greener” vacations to many SIDS. Some operators demand a “green” component to their vacation packages, although many vacations offered still involve very long flights to the SIDS destination.

The transportation patterns from European and American markets (and the emerging Chinese and other Asian markets) exaggerate long-haul flights – and therefore fuel consumption. While there is some capacity for SIDS in the Indian ocean to target closer markets such as India and the Middle East and for Caribbean SIDS to focus more on closer South American and southern North American markets, long haul is expected to continue to be a major component of their tourism, with limited capacity to reduce fossil fuel use, although if there are significant fuel price increases (or reductions), this may force some changes.

The impact of the cruise industry remains strong for many Caribbean and for other SIDS. Cruise visitors have stimulated the building of new ports, establishment of large numbers of shops and the growth of many local enterprises serving the needs of the thousands who disembark the ships through tours, souvenirs and tourist services. Both produce jobs and demand for goods and services, even though the cruise tourism is essentially day tourism.

Tourism demand may dictate both the transport options for an SIDS and affect the ability to do other forms of commerce internationally. Outside tourist season there may be many fewer flights and few direct destinations. Many Caribbean island nations have direct long-haul flights only in the December to April tourism season and are accessible only through local connections (Windward Islands via Barbados or Antigua) out of season. Similarly, while a port like Charlotte Amalie or Philipsburg may have up to seven ships a day in season, cruise ships visit only occasionally in other months. A dilemma for many SIDS is whether to build for the peak season (which coincides with the peak for resort tourism) or to build to accommodate less than the peak numbers. Failure to accommodate peak demand may not be an attractive or practical option. For many SIDS where tourism is important much of the retail is seasonal – as all of the jewelry shops and curio shops close when the season ends. This is also true of many restaurants and services – including some of those also used by the local population like dry cleaning, car rental, boat rentals or clothing shops.

Tourists on cruise ships tend to concentrate visits on specific sites – those easily accessible in day trips from the pier. In most SIDS, this includes most of the attractive natural sites, cultural sites, gardens and beaches on the island. Typically, all the tour buses can arrive at once, putting pressure on roads, parking, toilet facilities and restaurants. For larger SIDS, or those encompassing several islands, the cruise traffic is clustered within a short distance from the cruise port(s), and more distant attractions will not be advertised for cruise arrivals. For those staying longer, more dispersed attractions (e.g., Blue Mountains Jamaica, or Fogo in Cape Verde) can be on the tourist agenda.

As with all destinations, the concentration of tourist activity places stresses on the most fragile and culturally distinct sites. In situations where there are only a few favored sites, (e.g. Brimstone Hill and the Cane Train in St. Kitts) careful organization of tours is needed to ensure that there are enough parking places and restaurant, bus or train seats, particularly on days when several ships visit.

For cruise tourism, the trend is towards larger ships and shorter tours. Seven days is the mode for cruises, and many new ships have more than 4000 passengers (the largest in 2015 have 5600 passengers and more than 2000 crew). Most follow seven day circuits in the Caribbean from December to April, then may redeploy to places like Alaska or the Mediterranean.

Outside the Caribbean and Mediterranean, the cruise industry is generally a less significant part of the tourism industry, although many SIDS do have some cruise visits. Cape Verde, Fiji, Seychelles and Tahiti receive some visits on around-the-world itineraries but for many of the Pacific SIDS, ships visit infrequently. A major growth focus for cruise tourism, now that some feel the Caribbean is saturated, is the Asian and Australian market, with most lines deploying more ships to the region. This is bringing Caribbean level pressures to more Pacific SIDS. (For example Tuvalu is still off the cruise agenda and the first ship MS Amsterdam arrived in Niue on Feb 1, 2011, immediately outnumbering the island’s population. More visits are now scheduled for this island and some of its neighbours.

Some of the SIDS have a well-developed long-haul tourist sector, based on unique resources and a well-recognized image related to the quality of the experiences. French Polynesia, Maldives, Seychelles and Samoa have benefited from a tourism niche which is willing to spend large sums to travel long distances for a high quality experience. This market segment is less cost conscious than most other tourism and willing and able to pay for quality. Increasingly “quality” is being seen to have a clean, green and ethical component.

Mass tourism (typically the low-cost package one-week tour to a beach) is still a very significant part of the market for many SIDS, particularly in the Caribbean. Dominican Republic, Cuba, Jamaica, Barbados, Antigua, Netherlands Antilles, USVI all have large scale package tourism which is highly competitive in the North American and European markets, and is also having some success in other seasons by targeting South American tourists. While this segment is very price conscious, and is high volume, there are many opportunities to create efficiencies in this market which will bring both economic and environmental benefits. Just retrofit of older hotels (so that it is possible to manage the temperature without having both the air conditioning on and the windows open – as was found in one large Bahamas hotel) can bring real benefits.

Sustainable tourism in relation to Clean Technology / Cleaner Industry / Energy

It is difficult to generalize about the state of use of clean technology either in the tourism industry or in SIDS. Some of the most advanced applications of clean technology appropriate to accommodation can be found in hotels and resorts in SIDS. A bidding process for new island resorts in the Maldives drew many proposals which could be characterized as state of the art – principally because it was clear to bidders that a significant percentage of the points to be allocated to bids was to be based on an environmental component. As a consequence, several of the bids featured extensive use of solar for lighting and water heating, real-time electronic monitoring systems for water use and energy, full grey water re-use, heat recapture from boilers which also burned most organic waste, passive systems to force conservation by guests, and training sessions for staff and information sessions for visitors. As well, designs which optimized use of wind, shade etc. to reduce need for air conditioning were proposed. This is not the case however for most tourism enterprises in SIDS.

Because many tourism enterprises are small, advanced practices are often little known, technologies not available or not of suitable scale, and revenues insufficient to allow investment in equipment or practices where the payoff period is likely to be long. There is also a structural disconnect between those who must invest and those responsible for day to day management. Most large scale resorts are owned by investors (local or foreign) but managed by large international chains like Sol Melia, Bahia Principe, Six Senses, Intercontinental, Golden Tulip, Raffles or Banyan Tree. Management appointments are normally short term as are management contracts. If investments in new technology are not realized during the life of the typical contract, neither the manager nor the chain will benefit from such investments. New split water systems, sewage treatment plants, retrofits for energy saving typically will not realize additional profits during these short contract periods. One of the most immediately profitable retrofits – and one which is most frequently done, is to put in automatic switches for lights or air conditioning; the repayment time for these is usually very short – ironically shortest in SIDS where energy costs are highest. Energy is expensive and must be imported to most SIDS (notable exceptions are the few who have petroleum resources themselves (Sao Tome e Principe, Trinidad) or like Curacao, Singapore or Bahrain have refining facilities for re-export.)

Tourists themselves can be part of the problem. In destination workshops on sustainable tourism held by the UNWTO in destinations including the Caribbean and South Asia, many hoteliers observed that the more a tourist pays, the less willing to make “sacrifices” he or she is. The tourist paying thousands a night for a penthouse, view apartment or over-water bungalow is more likely than most to demand fresh towels daily or more often, constant temperature, spas, water features, lights which are always on when a room is entered. (UNWTO 2004)

As a consequence, there is a growing market for sensor systems which can both maintain the desired conditions and also reduce energy use with no effort from the guest.

There are a number of factors which are likely to be more important in most SIDS than in other destinations.

- Most goods must be transported considerable distances to SIDS destinations, making the costs higher and limiting access to best practice. This applies particularly to sophisticated technologies like solar systems, bio-reactors, and electronic water monitoring systems. As well, few SIDS have easy access to technical advice, purchase of many of these technologies, servicing and training in management. Most Caribbean SIDS need to buy equipment in Miami, bring any specialized personnel in to design and install it, and, if anything malfunctions import the skilled repair personnel to fix it. Similarly, South Pacific SIDS will need to go as far abroad as Sydney or Honolulu for access to more energy efficient new technologies and Indian Ocean states typically need to obtain such technologies and help from Europe or Singapore.

- Waste disposal can be even more of a challenge than in other destinations. Some SIDS have no formal waste management in place. Locating disposal sites where there will not be damage to wetlands, aquifers or shore zones can be a challenge on small islands. For very small islands there may be no good site which is not going to visibly damage the landscape or contaminate the aquifer. Most commercial incineration technology is available either at enterprise scale, or at very large scale industrial units which may be too large for smaller SIDS. Regional or multi-island solutions do exist (old auto bodies and other metal waste are gathered throughout the Caribbean and taken by boat to Trinidad for disposal) and the Maldives have garbage boats and a garbage island which handles most of the waste which cannot be incinerated on each tiny island.

- Liquid waste management has unique challenges in very small islands. If water is treated and then disposed of into the sea it may quickly draw down limited water resources. Water which is not treated effectively can affect fragile reefs or contaminate the aquifer. Grey water needs to be seen as a valuable resource for some uses if suitably recovered and treated. In several of the South Pacific atolls, the Maldives, or Anguilla the island’s ecosystem is totally dependent upon a small freshwater lens which “floats” on top of the surrounding sea water. If the lens is depleted or drawn down, there is salinization. In the Mexican island of Cozumel the aquifer depletion results in water shortages each May (the end of peak tourism season) as the wells which draw freshwater begin to draw sea water. (Manning, Vereczi and Hanna 1999). Even efforts to provide sewage treatment can add to the problem – as water which would ordinarily re-infiltrate the aquifer is instead cleaned and then sent out to sea. Some islands are now investigating recuperation of such water – or at least improved use of grey water systems at the municipal scale.

For water and energy poor SIDS, cruise tourism does provide an alternative form of tourism which is less likely to deplete local water resources or energy supplies. Cruise ships normally bring their own water supply and provide their own energy source. While, in Alaska there have been efforts to reduce greenhouse gases from ships by having them plug in at dockside and turn off the engines this option will not likely be useful for most SIDS. In Alaska ports the ships are powered by hydroelectric power; in most SIDS the island is producing power the same way as the ships – burning fossil fuels so there is little to be gained. There are global initiatives involving the cruise ship industry in greening its own operations and also efforts to assess how the cruise industry can contribute towards issues like reef protection, fostering local conservation in destination ports and tour sites – notably Conservation International. (Conservation International, 2008). At the same time, the tourists who go ashore will add to the need for sanitation services, and may stress local sewage and water infrastructure.

2.2 Environmental and social issues and opportunities

The tourism industry is very vulnerable and volatile. Events such as hurricanes, (typhoons and cyclones), earthquakes, disease or unrest can instantly devastate an island’s tourism. As shown in the UNWTO study of Phuket after the 2001 tsunami, (Manning E., Manning M. and Vereczi, G. 2001) loss of revenues due to reduced tourism numbers after the event is past can far exceed the cost due to physical damage in both extent and duration. News of hurricane impact on one Caribbean island can adversely affect visits on many others, even hundreds of kilometers from the area affected. Rebuilding the infrastructure usually happens much more rapidly than the resurrection of the tourism industry and its employment. While cruise tourism can instantly reprogram visits to avoid problems – hurricane damage, social strife or high costs (e.g. fuel or port fees) the loss of tourist visits during and after the disaster can add to the losses in the destination.

Tourism is dependent on the maintenance of key assets (natural and cultural) which are the reason why visitors travel. If these are depleted or degraded, tourism diminishes and can even virtually disappear. Storm damage (Grenada) tsunami (Maldives, Seychelles) civil strife or disease can devastate a destination instantly and recovery can take many years. Therefore, it is important for destinations, particularly those where tourism is a major element in their economy, to both understand what assets they have (which places, experiences, cultural artifacts the tourism is based upon), the sensitivity of such assets to changes, planned or otherwise, and measures to sustain these assets in perpetuity. As well, for many in the most disaster-prone areas (major storms, volcanos, earthquakes, piracy) business resumption plans will also be important. Larger islands may be able to create distinct separate destinations and market them separately thereby reducing some of the risk should there be localized problems (Punta Cana, a resort destination in the Dominican Republic is marketed separately from Puerto Plata; both are popular destinations for North American tourists). Similarly Jamaica (Montego Bay, Ocho Rios, Negril) and Cuba (Varadero, Cayo Coco, Holguin) have been able to differentiate destinations within their territory. This option is not open to most SIDS just because of size and the existence of a single entry point. Even where there are several discrete destinations, many tourists do not recognize the separation so a significant disaster in one (a tropical storm, health risk, or civil strife) may well affect the image and marketability of all destinations in an SIDS or an entire region.

A very large proportion of tourism assets and related facilities in most SIDS are located on or near the coast. For low lying islands and atolls, all of the assets are in the zone of greatest risk to impact of events which may be related to climate change. Storm surges, sea level rise, greatest wave impacts, temperature extremes (coral bleaching) can damage key ecosystems such as wetlands, lagoons; the beaches, and reefs; these are the principal tourism assets for many SIDS. These areas also coincide spatially with areas most vulnerable to tsunami for many SIDS in earthquake prone areas.

Maldive Islands resorts like Angsana reef, shown above, are all less than two metres above sea level and vulnerable to storm surges and tsunami swells.

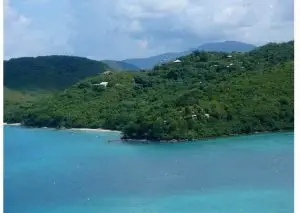

The zones with maximum vulnerability also coincide with the areas of greatest concentration of tourism related infrastructure. In SIDS (even those which are hilly or mountainous) nearly all airports are sited at coast; most include building on fill and runway extensions have been built into the sea; Over half of the SIDS with a single international airport fall into this category, and include for example, Barbados, Seychelles, Palau, and the British Virgin Islands. Many of the islands have ports with little storm shelter. Nearly all hotels and tourist facilities are built on the coast, concentrated on sandy beaches and building is normally well within the most vulnerable zones for storm surges, or tsunami.

Where risks to key natural and cultural assets and to the built assets of tourism are known, there are many approaches which can be used to reduce risk. Even on the smallest of islands there are actions which can be taken to adapt and to reduce the potential damage. As noted in the Maldives, where many resort islands are not much larger than a football field, actions have been put in place to limit the damage to reefs, aquifers and to native species at a resort level. Alterations to the reef which surrounds each island are normally forbidden. On most islands a central building (often a Mosque) is a designated shelter for storms, and is often the only hardened facility and the only building more than one story on the island. For most SIDS, it has been a challenge to influence building of resorts and hotels. Lines of tall hotels, with limited setbacks from the water occur in many SIDS, and in many there are no effective regulations to encourage more sensitive design, suitable setbacks from fragile beach and wetland systems and appropriate design to allow for storm surges and hardening of access points. While there are emerging models for more effective environmental planning for SIDS, (USVI, Maldives, Seychelles as examples) most SIDS do not yet have the comprehensive planning and enforcement capacity (note that this is a universal problem globally and not limited to small, island, or even developing states). What differs is the relative importance of tourism and its potential to catalyze solutions. This is largely unrealized. In the sections below some of the barriers and opportunities for SIDS are examined.

Because so many of the visitors to SIDS arrive in dedicated transport (charters, cruise ships) at a limited number of arrival points (for most there is one international airport and a single cruise port) there is an opportunity to contact travellers and inform them of the ecology and culture prior to their arrival. Some charter carriers have permitted tourism authorities to show information videos on inbound flights – for example a WWF sponsored short film on reef life and reef behavior on charter flights from Canada to Cuba. This opportunity has not often been capitalized upon, and newer types of seatback entertainment on recent planes may have removed the opportunity to contact all arrivals systematically. At the same time, single ports of entry can provide poster advice on environmentally sound or socially acceptable behavior (dress which doesn’t offend the local culture, rules against purchase of coral souvenirs etc.). To date these briefings do not tend to extend to advice regarding personal green practice – such as water or energy conservation. Most cruise lines do provide voluntary port briefings to passengers before each port, and many of these contain some environmental and cultural information as well as advertising for portside shops. (As a negative observation, few port specialists on cruise lines provide information on local crafts, shops or attractions which are not associated with the cruise tours or which are not part of large chains that have paid for advertising and very few advise on environmentally sound behaviors). This can diminish the net benefit to local craftsmen and shops deriving from cruise visitors and miss the opportunity to reduce negative impacts from tourist actions. (Note – some ships briefings do advise tourists to take their own water ashore and also to bring back the bottles). (For further discussion of the range of cruise ship and shore visitor impacts on small islands see

Managing Cruise Ship Impacts: Guidelines for Current and Potential Destination Communities

- Description of the Tourism Sector as a Business

In the introduction to this chapter the different parts of the tourism industry were delineated and the international and vertical linkages outlined. As noted, there are three parts of the industry which need to be treated separately – large international hotel resort and operational chains, the cruise ship industry and the SMEs which constitute the largest numbers of enterprises –including small hotels, guest houses, restaurants, tour and transport operators. The larger enterprises have generally begun to take advantage of the green economy. The smaller ones often lack organization, capacity to define opportunities and access to technical and financial support. While best practices suitable for large resorts, cruise ships or large hotels can be found in many of the chains present in SIDS, much of this is not easily transferrable to smaller enterprises at a suitable scale or in a form which does not require extensive training to install and maintain. At the same time there is growing anecdotal and survey-based evidence that tourists seeking the environmental and culturally distinct destinations found in most SIDS are willing to play more for these experiences. Detailed studies of whether they in fact do pay more and how sensitive this element is to types and quality of the environmental/cultural experience are still needed.

- The case for investing in the greening of tourism (The economics of investing in tourism and ecosystems).

Is there a case for investment in greening of tourism? The answer is a qualified yes. There are good success stories from all aspects of the industry and benefits accruing both to those within the industry and in SIDS destinations. At the top of the food chain are specialty properties such as Six Senses Soneva Fushi (Maldives) Cousine Island (Seychelles) Negril Tree House Inn (Jamaica) Jean-Michel Cousteau Fiji Islands Resort (Fiji) or Hotel Mocking Bird Hill(Jamaica) all of which have received recognition for best sustainable or green practice. Rates at resorts like these can exceed $2000 per night demonstrating that there is a top end market for high quality green properties while others have more modest pricing but must be booked well in advance, even out of season. For other segments of the tourism industry the benefits may be more difficult to see. It is generally agreed that there is a market for green (most tourists seem to consider green, clean and natural to be positive attributes for a hotel or resort), and many hoteliers have found that the green/non-smoking floor sells out first but there is little more than anecdotal evidence for the strength of the green or eco-market.

Maho Bay Eco Resort, Saint John USVI is recipient of many international awards for best practice.

Many of the most prestigious hotel and resort chains have concluded that there is merit in being seen to be green and advertise their environmental policies and practices on their websites – including for their properties in SIDS. The incentive for more conventional hotel and resort properties to become more sustainable is normally economic, as few SIDS have strong regulation requiring hotels to have, for example, Environmental Management Systems or conservation programs. Actions which reduce energy and water use can be very financially beneficial; water system separation and energy retrofits (particularly when replacement or renovation is scheduled) can pay off in short term – as little as two or three years for many renovations and for simple retrofits (better shades and switches which turn off lights and air conditioning) in less than six months. The payoffs are likely to be most visible where hotels and resorts either make their own electricity or must purchase it at high prices – a condition found in many SIDS. Similarly, water retrofits are most beneficial where water costs are highest – such as where a resort must desalinate its own water. Use of new technology is beginning – for example the use of wind turbines but some tourists object to what they consider visual pollution and in many SIDS, average wind speed is quite low making current wind turbines not cost effective. As noted earlier, the equipment and capacity to install these kinds of systems is in short supply in SIDS. There are also perceptual barriers. Many Maldives resort managers understood the advantage of solar panels, but were reluctant to deface the “grass hut” ambience of the rooftops of their resorts – in a destination where most visitors see the resort first by air as they arrive by sea plane. Initiatives by International players like the Global Sustainable Tourism Council to develop certification standards for destinations as a whole, as well as for specific properties may catalyze more destination level greening in future. As noted earlier, many of the larger chains already understand the merits of the green-blue economy and are moving to green their own properties; some are the catalyst for broader greening of destinations promoting better protection of beaches, garbage collection, and effective protection of the ecosystems on which their profits are based.

While there are a number of small Eco lodges and properties catering directly to those seeking a low impact natural experience in many SIDS (the tourism image marketed for Belize, Dominica and St. John USVI as examples trade on this) a majority of smaller properties in SIDS are not very involved in activities aimed at becoming more sustainable. Accommodation is provided in small lodges and homestays, with limited income and therefore little economic capacity to invest in any significant improvements, including green ones. For tours, in most destinations a range of nature oriented options can be found. Often, however, the tours offered include off road vehicles on beaches or through jungle, fast boat rides and parachuting behind boats, and even those which at the attraction itself may offer low impact experiences such as trail walking, wildlife watching or canoeing, will likely use diesel bus transport to get the tourists to the site.

While there are transportation options which are now in use which have lower GHG production, most are electric – and will draw on the grid. While, according to GENI some SIDS have potential for solar, wind, geothermal or hydro power, little of this has yet been realized and the source for transport fuel remains predominantly imported fossil fuels – see Renewable energy essential for well-being of small island developing states

For outstanding natural sites there are examples of best practice in conservation supported by the tourists who visit. At the Asa Wright Center in Trinidad, which is considered to be one of the premier bird watching sites in the hemisphere, revenues from the accommodation contribute to the conservation of the site in the Northern Range. High quality cabins are expensive and normally need to be reserved well in advance for peak birding seasons. Opportunities for similar eco-experiences exist in many other SIDS with their unique indigenous species.

Can the tourists and operators contribute to site management and protection? The privately run Asa Wright Centre shown in the picture above is one model as is North Island and Fregate Island in Seychelles. Many attractive botanical gardens (e.g. Romney Manor St Kitts, National Botanical Gardens Seychelles) are well maintained tourist attractions and do charge visitors entry. Bus tours from cruise visits also pay for entry. For less formal attractions – beaches, national forests and parks with free entry in many SIDS (El Yunque Puerto Rico, most beaches in Antigua or Seychelles, there is no direct contribution from visitors to the costs of site management and for protection of key assets. Where there is an effective method to tax visitors (for accommodation, access, or transport) and to channel some of that revenue for environmental protection and site management tourism can be a positive contributor. Where such systems are lacking, key assets can be degraded. There are some emerging examples of both tour operators and resorts that essentially “adopt” such key assets as local traditional communities, fragile natural sites or beach areas and contribute directly as part of their corporate management – and advertise that they do. Most of the resorts cited earlier in this chapter have such a program, and a majority also offer visitors the option of actively contributing to elements of the program – reef protection (Maldives), turtle protection (many Caribbean resorts, helping a local community with a specific problem like training in skills needed to get jobs in tourism or in guiding, or direct offsets like tree planting.) There is little reliable data on the level of uptake and contribution of this approach.

2.5.1 Spending in the tourism sector. Because different SIDS are at different stages in developing tourism products and those who are present have used different strategies for positioning their products, spending varies greatly from state to state. At one extreme, French Polynesia and Maldives have focused principally on a limited offer of high end tourism products. The cost to get there is very high and the cost per night to stay is in most cases at the high end of the market. Over water bungalows can cost several thousand dollars a night. Most of the properties are at least in part owned and/or operated by international companies. One issue is the leakage – as much of the spending is for goods purchased abroad and salaries which leave the country, as do profits. In some SIDS the wages of workers may also leave and there may be little contact with locals from whom goods or services could be bought. ( e.g., in the Maldives, many tourism workers are migrant workers from other south Asian countries – due to cultural factors which have led to a degree of separation of tourist islands from those where Maldive citizens reside.) At the other end of the spectrum are destinations which have courted lower-end mass tourism. Many properties in the Bahamas, Dominican Republic, Jamaica or Sint Maartin court low cost all inclusive visitors from North America with prices often as low as $700US for a week including air fare and food. The margins are very low for this type of vacation with much of the spending being for charter air fare, and goods including food brought from abroad. The revenues which remain in the country principally include wages for non-management staff, and limited local purchase (for example locally bottled liquor and soft drinks). Few thorough analyses have been done to clearly document the net social benefit from development and in particular from the tourism component. One reason is that a thorough social benefit cost analysis using border costs (even though SIDS would be the best laboratory for this) couls be prohibitively expensive. As well there is limited hard evidence of actual higher levels of spending for green experiences, despite the examples of best practice cited earlier.

2.5.2 Benefits in employment. Because of the difficulties in determining the net benefit of tourism to any nation, the UNWTO has developed a process of calculating tourism satellite accounts – which can help in at least estimating the value of tourism income and expenditures. Of the SIDS, only Cuba has published results from a national tourism satellite account. In the tourist section of the Green Economy report (p 423) some multipliers for employment were presented for SIDS with multipliers ranging from 4.61 for Jamaica to less than 2 for tourism jobs in (Western) Samoa or Palau – showing that for each person employed in tourism the overall effect on total employment can vary greatly. As noted earlier, size of SIDS is important; those like Jamaica or Mauritius can provide some of the needs of tourists locally (furniture, beverages, transportation equipment, skilled labor) and tend to show much higher multipliers than smaller states where nearly everything must be imported. Data on number of jobs created by tourist expenditure is also an issue. For most SIDS there is not much data available; for those where there have been estimates, the number of jobs per $10,000 US spent by tourists range from 0.79 for Fiji and 1.28 for Jamaica. For those SIDS where tourism is the predominant sector, in reality nearly all jobs may relate at least in part to the fortunes of tourism. While hotel schools have been put in place in many SIDS (e.g Barbados, Jamaica, Mauritius) those who wish training in most SIDS will need to leave to obtain it, and sustainable tourism curriculum is not generally available to obtain the skills needed to install or maintain greener equipment or methods.

- Local economic development and poverty reduction. Tourism has potential to stimulate some local economic development and to benefit local residents. In much of the tourism sector the issues above regarding the organization of the industry and the foreign ownership of major players has meant that local jobs have been in less skilled areas – such as groundskeepers, chamber maids, or other low paid service jobs. The trend towards all-inclusive resorts has also tended to limit the amount of money spent outside the resort boundaries. Even so, many small enterprises, local guiding and tour operators and arts and crafts sales do benefit from tourist spending. Some of the resorts have programs to aid local communities and to help develop micro-enterprises which will host tourists or try to develop products for sale to tourists. While not in a SIDS, the experience of the Bee Farm in Panglao Island Philippines is instructive – where a local enterprise initially selling honey grew to be the prime place to go and eat near the resorts on the island – marketing directly to the tourists on the beach and providing training to locals in craft production, and food services.

2.5.4 Environmental benefits. There are many individual success stories in conservation, greening, and contribution to preservation at the resort or Eco lodge scale. The range of actions which are seen as criteria for certification is summarized from several certification programs in table 3 above. As noted in earlier sections, several resorts and hotels in SIDS have qualified for certifications, satisfying one or more of the standards cited in the table. Some have also received awards from for example the Ecotourism Society or have received a range of industry recognitions for green practice. Most approaches to green certification focus on the property but initiatives under the Global Sustainable Tourism Council and private certifiers like Green Globe are beginning to develop criteria for overall destinations. These will likely be at a scale useful to SIDS. Increasingly there are also positive examples of contributions by the tourists themselves and by operators in protection of the key sites visited by the tourists – both by charging for entry or by mobilizing tourists themselves to contribute – through opportunities to do clean up, plant trees etc. or by financial contribution to local NGOs. Six Senses (with properties in several SIDS) has programs helping in preservation in all its localities, as does Banyan Tree. These are but a few of the resort chains which are increasingly implementing such programs, in addition to their on-site greening activities.

| Table 3 Criteria | Best Practice Standards (synthesis of the existing programs) (based on certification criteria from Green Globe 21. Certification for Sustainable Tourism (US) , Green Leaf/Audubon( Canada),Green Tourism Business Scheme(UK) ,Swan Ecolabel (Nordic) and Blue Flag Caribbean. Note: many SIDS properties now have one or more of the above certifications. |

| Project/product planning | · Formal planning process which addresses ecological and social factors, has environmental standards or review process, site plan review

· Formal review procedure (possibly with community participatory element), |

| Construction | · Design standards for siting, design compatibility. aesthetics, impact reduction re ecological and cultural values

· Construction standards for site disruption during construction, debris, site clean-up · Selection of local/suitable materials re protection of species, energy reduction, local benefits · Accessible design |

| Sewage/liquid waste management | · 100% treatment of wastewater through either reticulated system to treatment plant or self-contained treatment (option to use composing or contained systems as long as all waste is removed to a suitable disposal facility)

· Stormwater – separation, controlled runoff, (encourage grey water re-use, water consumption reduction, use of natural systems for cleaning where appropriate) |

| Water Conservation | · Must have water management plan – to include technical measures (low flow toilets, showers) grey water recycling, education and awareness, laundry reduction programs etc., ( In water short areas, use of water quotas and pricing, elimination of baths, sprinklers, or grey water reuse for irrigation.

· Must meet potable water standards for drinking water. (can have separate systems for drinking/cooking) |

| Energy Conservation | · Energy management plan which has elements of minimization of fossil fuel use, energy savings in washing, lighting, use of air conditioning and heating, (standards to reflect what is locally available or can be acquired |

| Air Quality | · Program /audit to minimize use of fossil fuels. |

| Noise | · Program to limit engine, tourist noise in areas sensitive to natural environment and wild animal behaviour. |

| Solid Waste Management | · Waste reduction and recycling programs required with goals monitored and recorded. Range of approaches can be used, see examples from Green Globe, Green Leaf, Nordic, Blue Flag |

| Materials re-use and recycling | · Require monitored program for separation, composting, recycling emphasized for organic and inorganic waste. Re-use and recycling done for all suitable commodities (where market for waste can be found or developed |

| Products and Purchasing | · Program to seek local products, products which can be recycled or re-used. Regular monitoring of consumption. Consider use of third party waste audits or certification programs familiar to key clients (e.g. if target is Nordic guests use their program criteria) |

| Food – sourcing | · Menu should contain/favour locally purchased foods, local cuisine. Over longer term seek National recognition for local/national cuisine. |

| Food – reduction | · Separate and recycle/compost organics as part of overall waste reduction program. (includes using plant waste as animal food) e |

| Beach | · (if applicable) Siting of structures and activities should meet ecologically based standards which recognize site sensitivities. |

| Community | · Indicators/monitoring put in place for key assets and fragile systems. |

| Partnerships | · Appropriate process established to involve local community in planning and oversight process and to facilitate ongoing linkages between tourism property and surrounding residents. |

| Cultural Sensitivity | · Plans/programs should involve local suppliers/guides etc. – specific plan for this linkage (clear attempt to involve local historic and cultural representatives where these exist) |

| Environmental Management System | · Facility should have EMS in place – beginning with the planning process and risk assessment. This should be the integrating framework for all of the plans and efforts contained in this list. (ideally has third party validation – maybe via international certification) |

| Training | · Must have a Training program re EMS and its components, and specific training modules for e.g guides, interpreters, groundskeepers, hotel staff |

| Operator Behaviour | · Information program for tourists, effort to direct tourists to trained guides and eco-sensitive tours, training for guides and operators linked to the facility (required, given) |

| Wildlife | · Program contains specific plans/actions to promote conservation, particularly in the ecosystems occupied or used. Participates in and/or supports protection of natural protected areas. Specific actions protect flora and fauna from extraction. Complies with trade laws on selling illegal products. |

| Conservation | · See wildlife above. Opportunities provided for visitors to contribute financially or otherwise to habitat conservation. |

| Natural Experience | · Marketing and pre-visit materials stress natural /sensitive tourism and appropriate tourist behaviours |

| Marketing | · Marketing plan which identifies correctly the ecological nature of the product and experience and shows expectations of the experience and behaviours. Educational element |

| Guest Education | · Guests informed of conservation, recycling and specific environmental measures adopted by property. Manual provided with sustainability mission and policies. Communication and involvement of guests in conservation efforts. Info on local plant species, natural areas. |

| Tourist Satisfaction | · Monitor and maintain guest satisfaction, re: ecotourism authenticity and quality of experience. |

| Monitoring Program | · Regular monitoring activities, monthly for energy use, regular monitoring of waste in kg/month, biodiversity action plans, natural or built heritage, advertising and marketing activities. |

The packagers of tours are also increasingly asking for visible response to international standards, which include an environmental component. There is a growing impetus (strongest in Europe) for ethical behavior from businesses including greater respect for ecosystems and cultures, and this is affecting the tourism sector. Through such initiatives as the Tour Operators Initiative and a range of certification standards it is becoming easier for tourists who wish to choose environmentally and socially responsible properties to find them. See The Tour Operators’ Initiative – a partnership involving UNEP, UNESCO, UNWTO and the tourism industry

For beach destinations the widely recognized Blue Flag program is one of the world’s most successful certification programs. (Blue Flag 2011). A third party certification program for beaches, it is well known in Europe and it spreading to other destinations – with adaptations suitable to areas like the Caribbean. What is certified is effective management, cleanliness and available services. Blue Flag certification is a strong element in marketing clean environmentally sound beach vacations. It is emerging as an effective means to demonstrate more environmentally sound management in a way which has good market recognition, particularly for tourists from Europe.

2.5.5 Cultural heritage Where there is built heritage it is usually part of the tourism agenda. Forts like San Felipe del Moro in San Juan, Puerto Rico, old towns like Old Havana Cuba or authentic local villages are targets for tours. Cultural events often are arranged for tourists (e.g., Creole experiences in Seychelles, visits to villages in Fiji or Dominica). Some of the revenues to maintain the cultural heritage is contributed by tourists through their tour and entry fees. From a greening perspective, heritage buildings are a difficult challenge as historic materials may not serve well to insulate and preservation skills may be lacking.

Regulations can limit use of new materials. Retrofit of historic architecture is possible and experience in, for example, Bermuda, shows many good models. Traditional island architecture, with for example Demerara shutters (Guyana) building on stilts and using flow through ventilation can be a positive model – both for cultural and environmental reasons. It can also be argued that many low impact low energy traditional lifestyles of the South Pacific or Caribbean (traditional foods, building methods, local non-acquisitive lifestyles) can be positive cultural models worth considering.

2.5.6 Modelling tourism

While methods are emerging to more clearly identify the real contribution of tourism (such as the satellite accounts noted above) generally inter-industry tables which could identify the relationship between tourism and the green economy do not exist, particularly for smaller states. Bahamas, Cuba, Dominican Republic Jamaica and Singapore are the SIDS which have begun work on tourism satellite accounts and initial data is available on the UNWTO site only for Cuba. See SDG Indicator s for “Sustainable tourism”