Is a car-free future possible?

These major cities are starting to go car-free

In late 2016, Madrid’s Mayor Manuela Carmena reiterated her plan to kick personal cars out of the city center.

On Spanish radio network Cadena Ser, she confirmed that Madrid’s main avenue, the Gran Vía, will only allow access to bikes, buses, and taxis before she leaves office in May 2019. It’s part of a larger effort to ban all diesel cars in Madrid by 2025.

But the Spanish city is not the only one getting ready to take the car-free plunge. Urban planners and policy makers around the world have started to brainstorm ways that cities can create more space for pedestrians and lower CO2 emissions from diesel.

Here are 12 cities leading the car-free movement.

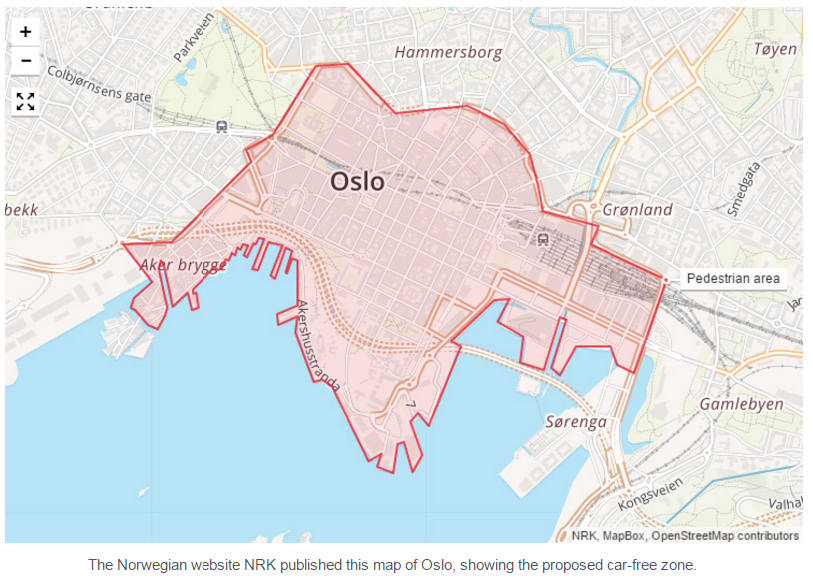

Oslo will implement its car ban by 2019.

Oslo plans to permanently ban all cars from its city center by 2019 — six years before Norway’s country-wide ban would go into effect.

The Norwegian capital will invest heavily in public transportation and replace 35 miles of roads previously dominated by cars with bike lanes.

“The fact that Oslo is moving forward so rapidly is encouraging, and I think it will be inspiring if they are successful,” says Paul Steely White, the executive director of Transportation Alternatives, an organization that supports bikers in New York City and advocates for car-free cities.

Madrid’s planned ban is even more extensive.

Madrid plans to ban cars from 500 acres of its city center by 2020, with urban planners redesigning 24 of the city’s busiest streets for walking rather than driving.

The initiative is part of the city’s “sustainable mobility plan,” which aims to reduce daily car usage from 29% to 23%. Drivers who ignore the new regulations will pay a fine of at least $100. And the most polluting cars will pay more to park.

“In neighborhoods, you can do a lot with small interventions,” Mateus Porto and Verónica Martínez, who are both architects and urban planners from the local pedestrian advocacy group A PIE, told Fast Company. “We believe that regardless of what the General Plan says about the future of the city, many things can be done today, if there is political will.”

People in Chengdu will be able to walk anywhere in 15 minutes or less.

Chicago-based architects Adrian Smith and Gordon Gill designed a new residential area for the Chinese city. The layout makes it easier to walk than drive, with streets designed so that people can walk anywhere in 15 minutes.

While Chengdu won’t completely ban cars, only half the roads in the 80,000-person city will allow vehicles. The firm originally planned to make this happen by 2020, but zoning issues are delaying the deadline.

Hamburg is making it easier not to drive.

The German city plans to make walking and biking its dominant mode of transport. Within the next two decades, Hamburg will reduce the number of cars by only allowing pedestrians and bikers to enter certain areas.

The project calls for a gruenes netz, or a “green network,” of connected spaces that people can access without cars. By 2035, the network will cover 40% of Hamburg and will include parks, playgrounds, sports fields, and cemeteries.

Bikes continue to rule the road in Copenhagen.

Today, over half of Copenhagen’s population bikes to work every day, thanks to the city’s effort to introduce pedestrian-only zones starting in the 1960s. The Danish capital now boasts more than 200 miles of bike lanes and has one of the lowest percentages of car ownership in Europe.

The latest goal is to build a superhighway for bikes that will stretch to surrounding suburbs. The first of 28 planned routes opened in 2014, and 11 more will be completed by the end of 2018. The city has also pledged to become completely carbon-neutral by 2025.

Paris will ban diesel cars and double the number of bike lanes.

When Paris banned cars with even-numbered plates for a day in 2014, pollution dropped by 30%. Now, the city wants to discourage cars from driving in the city center at all.

As of July 2016, all drivers with cars made before 1997 are not permitted to drive in the city center on weekdays. If they do, they will be fined, though they can drive there freely on the weekends.

The mayor says Paris also plans to double its bike lanes and limit select streets to electric cars by 2020. The city also continues to make smaller, short-term efforts to curb emissions — its first car-free day was in 2015, and it instated a car-free Sundays rule in May 2016.

Athens is also joining the diesel ban.

In December 2016, Athens, Greece announced it will ban diesel cars from the city center by 2025.

The initiative serves as an attempt to improve the city’s air quality. Athens already restricts diesel vehicles from the city center on certain days based on their plate numbers, but Athens Mayor Giorgos Kaminis says his goal is to eventually remove all cars from the area.

London will charge you for congestion.

Just like Paris, the mayor of London says the city will ban diesel cars by 2020.

Currently, the city discourages the use of diesel engines in some areas of the city by charging a fee of $12.50 per day for diesel cars that enter during peak hours. They call it a “congestion charge.”

“London is already talking about an ultra low emission zone, banning all sorts of diesel vehicles,” Stephen Joseph from the Campaign for Better Transport toldThe Telegraph. “This is not unlikely that they will be banned altogether in the same way Paris has done.”

Brussels features the largest car-free area in Europe.

Most streets that surround Brussels’ city square, stock exchange, and Rue Neuve (a major shopping street) have always been pedestrian-only. The roads make up the second largest car-free zone in Europe, behind Copenhagen.

In 2002, Brussels launched its first “Mobility Week,” which was meant to encourage public transportation over private transport. And for one day this September, all cars will be banned from the entire city center.

The city is looking for more ways to expand its car-free zones — one proposal would turn a popular four-lane boulevard into a pedestrian-only area. In February 2016, Brussels announced that diesel cars made prior to 1998 will be banned starting in 2018.

Mexico City hopes to ban about two million cars from the city center.

In April 2016, Mexico City’s local government decided to prohibit a portion of cars from driving into the city center two days every work week and two Saturdays per month. It determines which cars can drive on a given day using a rotating system based on license plate numbers.

According to the Associated Press, the policy applies to an estimated two million cars and helps to mitigate the city’s high smog levels.

Vancouver is giving more street space to bikes and pedestrians.

While many of the aforementioned cities have enforced car bans, Vancouver has persuaded an increasing number of residents to commute by public transport.

As Citylab notes, people in Vancouver take half of all trips by foot, bike, bus, or subway as of 2015. This is considerably more than any US city of comparable size, including Seattle (21%) and Philadelphia (27%), according to a 2015 United Nations report.

The city’s car-free movement might have been spawned by urban design decisions, according to the nonprofit Streetfilms, which recently interviewed key planning officials. Efforts include turning part of a major avenue, called Granville Street, into a pedestrian mall in the 1970s and expanding the bike lane network in 2008.

The city also hosts a car-free day every June, when it bans cars from busy blocks and sets up a street festivals.

New York City is decreasing car traffic in small doses.

Though New York City isn’t planning a car ban anytime soon, it is increasing the number of pedestrian areas, along with bike share, subway, and bus options.

Strips of land in popular areas like Times Square, Herald Square, and Madison Square Park are permanently pedestrian-only. On three Saturdays in August 2016, hundreds of thousands of people will take advantage of Summer Streets, an annual event that prohibits cars from driving on a major thoroughfare connecting Central Park to the Brooklyn Bridge, and opens roads for pedestrians.

“This is what everyday life could look like as if people mattered,” says Paul Steely White. “The worst thing as an urban dweller is to be stuck with the auto as your only option.”

Transportation Alternatives also hopes to work with the city to create more pedestrian plazas. White says urban planners are no longer trying to optimize New York City and other places for drivers, and are instead thinking about cities differently.

“Cities are coming to the realization that they need to swing the pendulum the other way,” he says.

Leave a Reply